The Father-Son Relationship: Time, Causality & Divinity

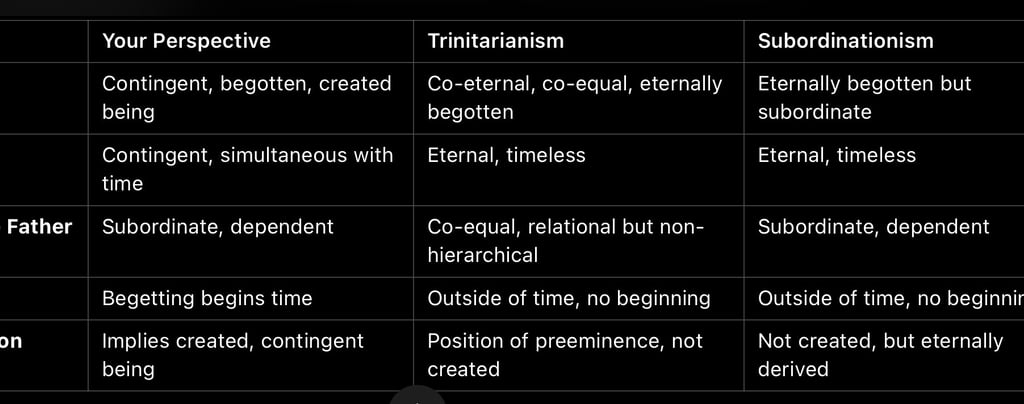

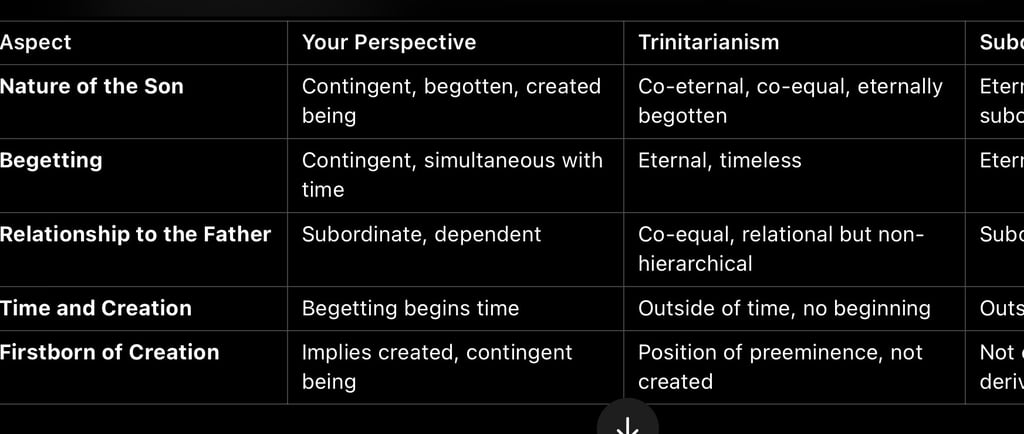

Had to write this essay to respond to the CRYING; I wanna fight when I lose an argument Himmy the CRYING Christian who think violence makes him right. Masking insecurities with violence is not godly or manly………………. The essay provides a philosophically rigorous and biblically grounded alternative to traditional Trinitarianism and Subordinationism by arguing that the Son is a contingent, begotten being, whose generation coincides with the beginning of time itself. Unlike Trinitarian doctrine, which asserts the eternal generation and co-eternality of the Son, and Subordinationist thought, which also struggles with the concept of timeless causality, this perspective resolves these tensions by affirming that begetting inherently implies contingency and temporality. Key arguments include: • The simultaneity of the Son’s generation with the creation of time, resolving the paradox of causality outside time. • The compatibility of contingency and divinity, affirming that the Son is fully divine while being dependent on the Father. • A literal reading of Scripture (e.g., Colossians 1:15), which portrays the Son as the firstborn of creation, rejecting abstract interpretations that obscure His contingent nature. • A critique of timeless causality, exposing its philosophical incoherence and presenting a superior framework by defining time as the measurement of the sequence and order of events. By carefully analyzing early church fathers such as Tertullian, Origen, and Hippolytus, as well as relevant biblical texts, the essay constructs a clear and consistent hierarchical model of the Father-Son relationship. This approach preserves the Father’s unique status as the uncaused cause while affirming the Son’s contingent yet divine nature as the first and only being of His kind. This essay will interest those who are deeply invested in exploring the logical coherence, philosophical clarity, and scriptural fidelity of doctrines about the nature of God, the Son, and their relationship.

NATURAL T

James Cassel

1/21/202521 min read

The relationship between the Father and the Son has been one of the most significant theological questions in Christianity. My position is that the Son, while divine and of the same kind as the Father, is a contingent, begotten being, whose generation coincided with the beginning of time itself. This view diverges from both Trinitarianism and traditional Subordinationism by acknowledging the Son’s contingency and situating His generation as an event inseparably linked to the creation of time and the cosmos. I also believe that my view represents what the Subordinationists were attempting to articulate, particularly when they struggled to explain the eternal generation of the Son in a way that avoided logical and philosophical contradictions.

By grounding my position in Scripture, reason, and the writings of early church fathers, I will demonstrate that the Son is the first and only contingent being of His kind, distinct from Trinitarian co-eternality and traditional Subordinationist ambiguity.

1. The Son’s Begetting Coincides with the Beginning of Time

The Son’s generation, or begetting, is a contingent event that occurred simultaneously with the beginning of time. This is not the eternal, timeless generation described in Trinitarian theology but a real and distinct act of the Father. As the Gospel of John declares:

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (John 1:1)

This verse establishes two critical points: first, the Son (the Word) existed in the beginning, marking the start of time; second, the Word was both with God and of divine nature. By saying, “in the beginning,” Scripture ties the Son’s existence to the start of creation, not to some timeless, abstract relationship. The Son’s begetting and the beginning of time are simultaneous events, inseparably linked to the Father’s creative act.

Tertullian’s insights in Against Hermogenes (Chapter 3) strongly support this view by clarifying that certain roles and relationships of God—such as Fatherhood and Lordship—are contingent upon events that occur in time. He writes:

“We affirm, then, that the name of God always existed with Himself and in Himself — but not eternally so the Lord. Because the condition of the one is not the same as that of the other. God is the designation of the substance itself, that is, of the Divinity; but Lord is (the name) not of substance, but of power. I maintain that the substance existed always with its own name, which is God; the title Lord was afterwards added, as the indication indeed of something accruing. For from the moment when those things began to exist, over which the power of a Lord was to act, God, by the accession of that power, both became Lord and received the name thereof. Because God is in like manner a Father, and He is also a Judge; but He has not always been Father and Judge, merely on the ground of His having always been God. For He could not have been the Father previous to the Son, nor a Judge previous to sin. There was, however, a time when neither sin existed with Him, nor the Son; the former of which was to constitute the Lord a Judge, and the latter a Father. In this way He was not Lord previous to those things of which He was to be the Lord. But He was only to become Lord at some future time: just as He became the Father by the Son, and a Judge by sin, so also did He become Lord by means of those things which He had made, in order that they might serve Him.”

This passage powerfully reinforces the contingency of the Son’s existence. Tertullian explains that Fatherhood is not an eternal characteristic of God but a relationship that depends on the generation of the Son. Just as God becomes a Judge only after the existence of sin, He becomes a Father only after the existence of the Son. Thus, there was a time when God was not a Father because the Son did not yet exist.

Tertullian’s statement that “there was a time when neither sin existed with Him, nor the Son” directly affirms the contingency of the Son’s begetting. It aligns perfectly with my position that the Son’s generation is not a timeless reality but an event that occurs at the beginning of time itself. The act of begetting the Son marks the transition in which God becomes Father for the first time.

Several other early church fathers also support this understanding, explicitly affirming that the Son’s existence is contingent and had a beginning. For example, Tatian, in his Address to the Greeks, writes:

“The Logos was in the beginning, but there was a time when He was not. For the Logos came into being by the will of the Father.”

Similarly, Hippolytus, in Against Noetus, states:

“God was alone, and there was no one with Him. But when He willed it, He begot the Word.”

Both Tatian and Hippolytus affirm the idea that the Son’s existence is a result of the Father’s will, making His generation a contingent act rather than an eternal fact.

This stands in contrast to Trinitarian theology, which posits that the Son’s generation is an eternal, timeless relationship existing outside of time and causality. Such a view removes the contingency of the Son’s begetting and fails to address the logical implications of begetting as an act that requires a beginning. My view, supported by these early church fathers, maintains that the Son’s begetting is an event tied to time itself, inseparable from the creation of the cosmos.

2. The Son Shares the Divine Nature as a Being of the Same Kind

The Son, though begotten, shares the divine nature of the Father. This is consistent with the principle that things are begotten after their own kind, as C.S. Lewis writes in Mere Christianity:

“A man begets a child, but he only makes a statue. What God begets is God; just as what man begets is man.”

While I agree with Lewis that things are begotten after their own kind, I diverge from his Trinitarian view of the Son as co-eternal with the Father. In my understanding, the Son’s contingency does not diminish His divine nature but rather makes Him the only contingent being of His kind. The Son is divine because He is begotten by the Father, who shares His own nature with Him, but this does not require the Son to exist eternally.

Scripture also supports this distinction:

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (John 1:1)

Here, “the Word was God” underscores the Son’s divine nature. However, I take “God” in this instance to refer not to identity with the Father but to divine essence. The Son, being begotten, shares the Father’s nature but is not the Father Himself.

The early church father Justin Martyr, in Dialogue with Trypho, affirms this view:

“We reasonably worship Him, having learned that He is the Son of the true God Himself, and holding Him in the second place.”

Justin’s description of the Son as second to the Father reflects the idea that the Son is divine but not equal to the Father in status or existence. This understanding aligns with my position: the Son is begotten of the Father, shares His divine nature, and is of the same kind, yet remains contingent.

This perspective differs from Trinitarian theology, which holds that the Son’s divine nature necessarily implies co-eternality. In contrast, I argue that contingency does not negate divinity. The Son is divine because He is of the same kind as the Father, but His generation remains an act of the Father’s will, inseparably tied to the beginning of time.

3. The Father Is Greater Than the Son

The Father and Son exist in a hierarchical relationship, where the Father is the source of the Son’s existence. Jesus Himself declares:

“The Father is greater than I.” (John 14:28)

This statement unequivocally affirms the subordination of the Son to the Father, both in role and in being. The Father is the uncaused cause, the ultimate source of all things, while the Son is begotten, deriving His existence and nature from the Father.

Tertullian, in Against Praxeas (Chapter 9), expresses this relationship clearly:

“The Father is the entire substance, but the Son is a derivation and portion of the whole… Thus the Father is distinct from the Son, being greater than the Son, inasmuch as He who begets is one, and He who is begotten is another.”

Tertullian emphasizes that the Father and Son are distinct, with the Father being greater as the one who begets and the Son existing as the begotten. He further criticizes those who fail to understand this dynamic, calling them “perverse” for rejecting the obvious implications of the Father-Son relationship.

Trinitarian theology attempts to explain this relationship through the doctrine of eternal generation, but it ultimately undermines the clear hierarchy between Father and Son by asserting their co-equality. In my view, the relationship of begetter and begotten necessarily implies subordination, as the Son is contingent on the Father for His existence.

4. The Son as the Firstborn of All Creation

The apostle Paul describes Christ as:

“The firstborn of every creature.” (Colossians 1:15)

This verse supports my position that the Son is not only begotten but also a created being. The term “firstborn” indicates both priority and preeminence, affirming that the Son is the first act of creation and the means through which the rest of creation comes into being. Early church fathers such as Origen also affirm this interpretation:

“The Son, begotten of the Father, is the firstborn of all creation, and through Him all things were made.” (On First Principles, Book 1, Chapter 2)

By referring to Christ as the firstborn, Paul and the early fathers confirm that the Son’s begetting is an act of creation, distinguishing Him from the Father as a contingent being. This interpretation directly challenges Trinitarian claims of the Son’s co-eternality, instead affirming His begotten, created nature.

5. My View as a Clarification of Subordinationist Thought

While I disagree with certain articulations of eternal generation, I believe my view reflects what the Subordinationists were attempting to express. Figures like Origen and Tertullian emphasized the Son’s derivation and subordination to the Father but struggled to reconcile this with the idea of eternal existence. My perspective resolves this tension by acknowledging the Son’s contingency and situating His generation as a real event tied to the beginning of time and creation.

Conclusion

My position affirms that the Son is a contingent, begotten being, whose generation coincides with the beginning of time. Unlike Trinitarianism, which removes contingency from the Son’s existence, and Subordinationism, which struggled to articulate the Son’s eternal generation, my view provides a coherent explanation rooted in Scripture, reason, and early church writings. The Son is divine, of the same kind as the Father, yet subordinate and contingent, marking Him as the firstborn of all creation and the unique expression of the Father’s nature.

Trinitarian Doctrine: Eternal Generation and Co- Eternality

Trinitarian theology, as articulated at the Council of Nicaea (325 CE) and refined at the Council of Constantinople (381 CE), insists on the co-equality and co-eternality of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This doctrine hinges on the concept of the eternal generation of the Son. Below, I will analyze and critique the key tenets of this doctrine—eternal generation, co-eternality, and co-equality—and expose its philosophical weaknesses. I will demonstrate that my position, grounded in the contingent and begotten nature of the Son, resolves these issues more coherently.

1. Eternal Generation as a Contingent Event

Trinitarian doctrine posits that the Son is eternally begotten of the Father, meaning that His generation is not a temporal act but a timeless, eternal relationship. However, from my perspective, this attempt to remove contingency from the Son’s begetting fails to account for the inherent nature of the act itself. By definition, begetting implies a beginning—a moment when the one being begotten comes into existence. Even if we attempt to frame this act as “eternal,” it still remains contingent because it depends on the will of the Father.

Logical Argument from Contingency

1. Begetting, by nature, implies an act of causation: For the Son to be begotten, He must be caused or brought into existence by the Father.

2. Causation inherently implies contingency: The Son’s existence depends on the Father’s act of begetting, making Him a contingent being.

3. Timelessness cannot remove contingency: Even if we frame the act of begetting as “eternal,” the relational dependency of the Son on the Father for His existence remains. Thus, the act of eternal generation cannot logically be separated from contingency.

4. Conclusion: The Son’s generation must be understood as a contingent event, and the Trinitarian attempt to make it timeless only obscures the inherent dependency of the Son on the Father.

Early Church Fathers on Contingency

Several early church fathers affirm the contingent nature of the Son’s existence:

1. Hippolytus, in Against Noetus (Chapter 10), writes:

“The Word alone came forth from Him: but this was not by separation, but by generation. The Father remained entire, while generating the Word, and without loss to Himself.”

Hippolytus acknowledges that the Word (Son) came into existence through generation, emphasizing that this act was contingent on the Father’s will.

2. Tertullian, in Against Hermogenes (Chapter 3), states:

“For He could not have been the Father previous to the Son, nor a Judge previous to sin. There was, however, a time when neither sin existed with Him, nor the Son.”

This explicitly affirms that the Son’s generation is an event, not an eternal reality, further reinforcing its contingent nature.

3. Novatian, in On the Trinity (Chapter 31), writes:

“The Word is one also, by whom all things were made, who proceeded from the Father.”

Novatian highlights that the Word “proceeded” from the Father, implying a dependent, contingent relationship.

These early church fathers make it clear that the Son’s begetting is not timeless but a contingent event, tied to the will and act of the Father.

2. Co-Eternality and the Contingency of the Son

Trinitarian theology asserts that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are co-eternal, meaning there was never a time when the Son did not exist. From my perspective, this claim is logically inconsistent with the act of begetting. If the Son is begotten, then there must be a point—whether within time or simultaneous with its beginning—when the Son’s existence begins. The concept of co-eternality contradicts this fundamental reality.

Logical Argument Against Co-Eternality

1. Begetting requires a point of origin: To be begotten means to come into existence as a result of the begetter’s action.

2. Eternity precludes origin: If the Son is co-eternal with the Father, He would have no point of origin and thus could not be begotten.

3. Co-eternality and begetting are mutually exclusive: The Son cannot simultaneously be begotten and co-eternal with the Father.

4. Conclusion: The doctrine of co-eternality is illogical because it denies the contingent and causal nature of the Son’s generation.

Early Church Fathers on the Son’s Contingency

Early church fathers also rejected the notion of co-eternality:

1. Origen, in On First Principles (Book 1, Chapter 2), writes:

“The Son is generated by the Father’s will. The Father is unbegotten, but the Son owes His existence to the Father.”

Origen explicitly ties the Son’s existence to the will of the Father, affirming His contingency.

2. Eusebius of Caesarea, in Demonstratio Evangelica (Book 4, Chapter 3), states:

“The Father is the cause of the Son, and the Son is the first and only-begotten of the Father.”

This clearly shows that the Son’s existence is caused by the Father, precluding co-eternality.

3. Lactantius, in Divine Institutes (Book 4, Chapter 29), declares:

“God, before He undertook the construction of the world, begat a pure and incorruptible spirit whom He called His Son.”

Lactantius explicitly describes the Son’s begetting as a contingent act that occurs prior to creation, not as an eternal reality.

These quotes confirm that the Son’s generation is contingent on the Father’s will and action, which undermines the Trinitarian claim of co-eternality.

3. Co-Equality and the Hierarchy in the Godhead

Trinitarian theology holds that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are co-equal in power, glory, and essence. However, Scripture and early church writings consistently affirm a hierarchical relationship in which the Father is superior to the Son.

Biblical Evidence for Hierarchy

1. John 14:28: “The Father is greater than I.”

Jesus Himself declares the Father’s superiority, directly contradicting the Trinitarian claim of co-equality.

2. 1 Corinthians 11:3: “The head of Christ is God.”

Paul affirms that the Son is subordinate to the Father, placing God as His head.

3. 1 Corinthians 15:28: “Then the Son Himself will also be subjected to Him who put all things in subjection under Him, that God may be all in all.”

This verse explicitly states that the Son will be subjected to the Father, reinforcing the hierarchy within the Godhead.

Early Church Fathers on Hierarchy

1. Justin Martyr, in First Apology (Chapter 13), writes:

“We worship the Son in the second place, giving Him the second rank after the unchangeable and eternal God.”

2. Irenaeus, in Against Heresies (Book 2, Chapter 28), states:

“The Father is above all, and He is the head of Christ.”

3. Tertullian, in Against Praxeas (Chapter 9), declares:

“The Father is greater than the Son, and the one who begets is greater than the one who is begotten.”

These early church fathers affirm the hierarchical relationship within the Godhead, directly opposing the Trinitarian concept of co-equality.

4. Philosophical Implications of the Trinity Doctrine

The Trinitarian doctrine faces significant philosophical challenges, particularly in its attempt to reconcile eternal generation, co-eternality, and co-equality. These issues include:

1. Eternal generation contradicts contingency: The act of begetting implies causation and contingency, yet Trinitarianism denies this by making the generation eternal.

2. Co-eternality denies origin: If the Son is co-eternal, He cannot be begotten, as this would require a point of origin.

3. Co-equality denies hierarchy: Scripture and early church writings consistently affirm the Father’s superiority over the Son, making co-equality untenable.

My stance resolves these contradictions by affirming that the Son’s generation is a contingent, time-bound event that establishes a hierarchical relationship between the Father and the Son. This view is more consistent with Scripture, early church tradition, and logical reasoning.

Subordinationism: A Hierarchical but Contingent Relationship

Subordinationism, a pre-Nicene theological position, emphasizes the subordination of the Son to the Father while maintaining the Son’s eternal existence. Prominent figures like Origen, Tertullian, and Novatian articulated this view, which was later associated with Arianism and ultimately rejected by the Nicene Creed. Subordinationism affirms the divine nature of the Son while emphasizing His dependent and subordinate role to the Father.

While I share with Subordinationism its belief in the hierarchical relationship between the Father and the Son, I reject the notion of eternal generation as a timeless and abstract process. Instead, I argue that the Son’s begetting is a contingent event tied to the beginning of time, making Him the first created being of His kind. Below, I will expand on my agreements with Subordinationism, clarify where I differ, and provide a rigorous philosophical critique of its unresolved issues.

1. Agreement with Subordinationist Views

I agree with Subordinationism’s emphasis on the hierarchical nature of the Father-Son relationship. The Son is begotten of the Father, making Him dependent on the Father for His existence. This dependency inherently places the Son in a subordinate role. The early church fathers consistently affirmed this hierarchical relationship. For example:

• Origen, in On First Principles (Book 1, Chapter 3), writes:

“The Father alone is unbegotten, but the Son, begotten by the Father, is subordinate to Him in rank.”

• Tertullian, in Against Praxeas (Chapter 9), declares:

“The Father is greater than the Son, inasmuch as He who begets is greater than He who is begotten.”

These statements affirm that the Father is the ultimate source of the Son and superior in rank and authority. Subordinationism rightly identifies the Father as the head and the Son as the subordinate—a view that aligns with Scripture (e.g., John 14:28, 1 Corinthians 11:3).

However, I avoid terms like eternal subordination, as they risk confusing readers into associating the Son’s existence with an abstract, non-contingent reality. Instead, I affirm that the Son’s subordination is real, hierarchical, and contingent, rooted in His generation as the first act of creation.

2. Rejection of Eternal Generation

Where I diverge from Subordinationism is on the issue of eternal generation. Subordinationism maintains that the Son is eternally begotten by the Father, which is a cornerstone of its doctrine. However, I find this concept logically untenable because it fails to address the inherent contingency of the act of begetting.

Logical Critique of Eternal Generation

1. Begetting implies a beginning: The act of begetting, by definition, requires a starting point for the one who is begotten. If the Son is begotten, His existence must have a point of origin.

2. Eternal generation obscures contingency: Subordinationists attempt to reconcile the Son’s dependency on the Father with eternal existence by making the generation “timeless.” However, this fails to account for the intrinsic contingency of the Son’s existence, which depends on the will and action of the Father.

3. A timeless relationship negates causality: If the Son is eternally begotten, then there is no actual causal sequence between the Father and the Son. The Father’s role as the source becomes meaningless without a real act of causation.

4. Conclusion: Eternal generation contradicts the nature of begetting as a causal and contingent act. The Son’s generation must therefore be understood as a temporal event tied to the beginning of time, not an eternal process.

This critique is consistent with early church fathers who emphasized the contingent nature of the Son. For example:

• Tertullian, in Against Hermogenes (Chapter 3), writes:

“There was a time when neither sin existed with Him, nor the Son.”

Tertullian explicitly affirms that the Son’s existence had a beginning, rejecting the notion of eternal generation.

• Hippolytus, in Against Noetus (Chapter 10), states:

“The Word alone came forth from Him: but this was not by separation, but by generation.”

This emphasizes the Son’s contingent and caused existence, distinguishing Him from the eternal and uncaused nature of the Father.

These statements illustrate that eternal generation is inconsistent with the reality of the Son’s contingency.

3. Agreement with Ontological and Functional Subordination

I also agree with Subordinationism’s view of ontological and functional subordination, which holds that the Son is subordinate to the Father in both origin and role. The Son is begotten of the Father, meaning His existence is derived from the Father’s will. This places the Father in a position of ontological superiority as the uncaused cause.

Scripture provides clear support for this hierarchical relationship:

• John 14:28: “The Father is greater than I.”

Jesus explicitly affirms the Father’s superiority in this verse, which directly supports the Subordinationist view of hierarchy.

• 1 Corinthians 11:3: “The head of Christ is God.”

Paul reinforces the idea that the Father holds a higher position than the Son, both in origin and authority.

• 1 Corinthians 15:28: “Then the Son Himself will also be subjected to Him who put all things in subjection under Him, that God may be all in all.”

This verse demonstrates that the Son’s subordination to the Father is an enduring reality, not a temporary state.

Early church fathers also articulated this hierarchical understanding:

• Justin Martyr, in Dialogue with Trypho (Chapter 56), writes:

“The Father is greater than the Son, for He is unbegotten and uncaused, while the Son is begotten.”

• Novatian, in On the Trinity (Chapter 31), states:

“The Father is the one true God, and the Son is His Word, begotten and subordinate to Him.”

These writings affirm that the Son’s subordination is intrinsic to His relationship with the Father, consistent with both Scripture and reason.

4. Philosophical Issues and Why My Stance Is Superior

While I share much of Subordinationism’s framework, I deviate on the issue of eternal generation and the philosophical implications it raises. Subordinationism, like Trinitarianism, fails to resolve the inherent contradictions in attempting to reconcile the Son’s contingency with the concept of eternal generation.

Philosophical Issues in Subordinationism

1. Eternal generation negates contingency: By asserting that the Son is eternally begotten, Subordinationism attempts to remove the temporal aspect of His generation. However, this contradicts the very nature of begetting, which requires a point of origin.

2. The problem of timeless causality: Subordinationism posits that the Father is the cause of the Son, yet it frames this causality as eternal and timeless. This creates a paradox, as causation inherently requires a sequence of events.

3. Confusion of terms: Subordinationism uses terms like “eternal” to describe the Son’s relationship to the Father, but this conflates the Son’s contingency with the Father’s necessary existence. The result is a doctrine that obscures the true nature of the Father-Son relationship.

Why My Stance Is Superior

My stance resolves these issues by affirming that the Son’s generation is a contingent, time-bound event that marks the beginning of creation. This approach offers several advantages:

1. Logical coherence: By acknowledging the contingency of the Son’s generation, my view avoids the contradictions inherent in eternal generation and timeless causality.

2. Scriptural fidelity: My position aligns more closely with Scripture, which consistently portrays the Son as subordinate to the Father and dependent on Him for existence.

3. Philosophical clarity: By situating the Son’s generation at the beginning of time, I preserve the causal relationship between the Father and the Son without resorting to abstract, timeless concepts.

In conclusion, while I agree with Subordinationism on many points, my position provides a more philosophically rigorous and biblically consistent framework for understanding the Father-Son relationship.

Philosophical Implications of My View

My view of the Son as a contingent, begotten being, whose generation coincides with the beginning of time, offers a coherent alternative to both Trinitarian and Subordinationist doctrines. By rooting the Son’s generation in contingency and temporality, my perspective resolves inherent contradictions in traditional doctrines while preserving a biblically and logically consistent framework.

To clarify, time is defined as the measurement of the sequence and order of events. In this framework, time provides the structure within which causality operates, enabling a meaningful relationship between cause and effect. The philosophical implications of my view arise directly from this understanding of time and its relationship to the generation of the Son. Below, I explore the implications in four key areas: causality, contingency, scriptural fidelity, and timelessness.

1. Causality and Simultaneity

In my view, the Son’s begetting and the beginning of time are simultaneous events. This perspective challenges traditional notions of causality, which often assume a temporal sequence between cause and effect. Since time is the measurement of the sequence in order of events, it logically follows that causality cannot exist outside of time. Thus, by begetting the Son, the Father not only brings the Son into existence but also creates time itself—the framework within which causality operates.

Philosophical Implications:

1. Causality Requires Time:

For causality to exist, there must be a sequence of events—one event acting as the cause and another as the effect. Since time is the measurement of this sequence, causality is meaningless without time. By placing the Son’s generation at the beginning of time, my view preserves the causal relationship between the Father and the Son while situating it within a coherent temporal framework.

2. Simultaneity Avoids Logical Contradictions:

If the Son’s generation coincides with the creation of time, there is no “before” or “after” in which one might argue that the Son preexisted or that time existed without the Son. Instead, the act of begetting is the first cause that brings both the Son and time into existence. This simultaneity resolves the tension between causality and timelessness found in traditional doctrines.

Why This Is Significant:

Traditional Trinitarian theology attempts to frame the Son’s generation as a timeless act, but this creates a logical contradiction. If causality requires time, then a timeless cause cannot produce a meaningful effect. My view resolves this problem by grounding the Father’s causation of the Son within the beginning of time, preserving both the causal relationship and the logical coherence of the Father-Son dynamic.

2. Contingency and Divinity

My view explicitly acknowledges that the Son is contingent—His existence depends on the will and act of the Father. However, this does not diminish His divinity, as His contingency is unique and reflects the Father-Son relationship. The key lies in understanding that the Son, while contingent, shares the Father’s nature because He is begotten “after His kind.”

Philosophical Implications:

1. Contingency Does Not Negate Divinity:

The Son’s contingency highlights His dependency on the Father as the uncaused cause. However, as C.S. Lewis notes in Mere Christianity:

“What God begets is God; just as what man begets is man.”

The Son is divine because He is begotten of the Father, who shares His nature. This principle aligns with natural law, where offspring are of the same kind as their progenitors.

2. The Father’s Uniqueness as Uncaused:

The Father alone is uncaused and eternal, while the Son is caused and contingent. This distinction preserves the divine hierarchy without undermining the Son’s divinity. The Son’s contingency reflects His dependency on the Father while maintaining His status as the only begotten being of His kind.

Why This Is Significant:

Traditional doctrines conflate contingency with inferiority, attempting to remove contingency from the Son’s existence by framing His generation as timeless. My view avoids this error by affirming that contingency and divinity are compatible, as the Son derives His divine nature from the Father while remaining contingent.

3. Scriptural Fidelity

One of the strengths of my view is its alignment with Scripture, particularly passages that describe the Son as begotten, firstborn, and subordinate to the Father. For example, Colossians 1:15 states:

“He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation.”

The term “firstborn” (prototokos) implies both priority in order and preeminence, affirming the Son’s status as the first contingent act of the Father’s will. This interpretation aligns with early church fathers such as Origen, who writes:

“The Son is generated by the Father’s will, and through Him all things were made.” (On First Principles, Book 1, Chapter 3)

Philosophical Implications:

1. “Firstborn” Reflects Contingency:

The Son’s status as the firstborn highlights His priority as the first event in the sequence of creation, consistent with the definition of time as the measurement of the sequence in order of events. This further supports the idea that the Son’s generation is the first cause within time, rather than an eternal abstraction.

2. Literal Reading Avoids Doctrinal Confusion:

Traditional doctrines often reinterpret “firstborn” metaphorically to avoid the implication that the Son is created. However, this approach disconnects doctrine from the clear meaning of Scripture and creates unnecessary complexity.

Why This Is Significant:

My view upholds a literal and coherent interpretation of Scripture, affirming the Son’s contingent and subordinate role as the firstborn of creation. This approach maintains fidelity to biblical texts while providing a consistent framework for understanding the Father-Son relationship.

4. Critique of Timelessness and Why My Stance Resolves the Issues

Traditional theology’s reliance on timelessness creates significant philosophical challenges. Both Trinitarianism and Subordinationism attempt to reconcile the Son’s dependency on the Father with the concept of timeless, necessary existence. However, these approaches fail to account for the intrinsic nature of time and causality.

Philosophical Problems with Timelessness:

1. Causality Requires Sequence:

If time is the measurement of the sequence in order of events, causality cannot exist without time. Framing the Son’s generation as “timeless” eliminates the sequence necessary for cause and effect, making the Father-Son relationship incoherent.

2. Timeless Begetting Is Self-Contradictory:

Begetting, by definition, involves a process of bringing something into existence. Describing this process as timeless removes its intrinsic contingency and causality, rendering the concept meaningless.

3. Timelessness Undermines Hierarchy:

By framing the Father-Son relationship as timeless, traditional doctrines reduce the hierarchical distinction between the two to a nominal role. This contradicts both Scripture and reason, which affirm the Father’s superiority as the uncaused cause.

Why My Stance Resolves These Issues:

1. Grounding Causality in Temporality:

By situating the Son’s generation at the beginning of time, my view preserves the sequence necessary for causality. The Father’s act of begetting creates both the Son and the temporal framework within which causality operates.

2. Respecting the Divine Hierarchy:

My view affirms the Father’s role as the uncaused cause, preserving the real hierarchical distinction between the Father and the Son.

3. Logical Coherence:

By rejecting timeless causality, my view resolves the contradictions inherent in traditional doctrines and provides a consistent framework for understanding the Father-Son relationship.

Conclusion

The philosophical implications of my view demonstrate its superiority over traditional doctrines. By defining time as the measurement of the sequence in order of events, I affirm the Son’s contingent, time-bound generation as the first event in the created order. This approach resolves the contradictions of timeless causality and eternal generation, preserving the logical coherence, divine hierarchy, and scriptural fidelity of the Father-Son relationship.